I run games in two completely different modes.

On one side, there’s my Children of Fear campaign: a glorious monstrosity of prep. I’ve turned the book into episodic node graphs for an open table. Every chapter is broken into session-sized cards containing scenes and locations with arrows going everywhere. I have digital sticky notes, colour-coded tags, and more hyperlinks than the average conspiracy theory blog.

On the other side, there are sessions where I have: a loose concept, a few names, a rough idea of what might happen, and an unearned belief that Future Me will somehow make all of this coherent.

Here’s the good news, and the secret I wish someone had told me earlier:

From the players’ side of the screen, the super-prepped session and the totally improvised session often feel equally good.

They can’t see your notes. They just see whether things are moving, whether NPCs feel like people, and whether the consequences of their actions make sense.

This piece is about getting comfortable with that second style: improv at the table. Not “I’m a genius stand-up comedian riffing for four hours”, but “I can react without freezing, keep things coherent, and feel okay when it goes a bit sideways.”

I’m still learning this myself. Think of this as field notes from someone who’s fallen off this bike a lot and is now, mostly, falling off it with style.

Why Improv Feels Scary (and Why You Should Do It Anyway)

Improv feels terrifying because it attacks all our GM anxieties at once.

You’re afraid you’ll blank. You’re afraid you’ll contradict yourself. You’re afraid your players will see the moment your soul leaves your body as you realise they’ve just befriended a throwaway NPC you named “Old Gregg” on the spot and now he’s central to the plot.

Also, many of us learned GMing from big books with big plots. They give the illusion that if you just prep hard enough, you can avoid surprise. Then you actually play, and the players immediately run off the map, seduce the villain, and adopt the wandering monster as their son.

Here’s the thing: you can’t prep away surprise. Even very prep-heavy GMs recognise this. As Mike Shea (Sly Flourish) advises, “Prepare to improvise. The best scenes in D&D happen spontaneously.”

And he’s right. The moments we remember are the ones nobody planned.

You don’t need to stop prepping. You just need to prep differently so improv feels like surfing your notes, not leaping without a parachute.

Confidence First: Shrinking the “Oh No” Moment

The first goal isn’t “be brilliant on the fly”. It’s simply: panic for less time.

A few things that helped me:

Treat improv as filling in gaps, not replacing everything.

When I sit down to run, I still know roughly where we’re starting, who’s in the area, and what they broadly want. Improv lives in the “how” and “what exactly” of the moment. That’s much less scary than “make up an entire plot from nothing”.

Normalise saying “give me a second.”

You’re allowed to pause. I’ve started saying words to the effect, “Okay, cool, give me a moment to think what that looks like,” and jotting a quick note. I used to feel embarrassed about this but I saw better GMs doing it, so I got comfortable with my own taking a moment to think. Everyone takes a sip of their drink; nobody minds. The pressure to respond instantly is mostly self-inflicted.

Aim for “good enough now, better later.”

If an NPC motivation, clue, or twist isn’t amazing, that’s fine. You can deepen it retroactively by reincorporating it later. A throwaway line about an NPC’s brother can turn into a whole subplot two sessions down the line. Players will assume you meant it all along.

Remember your job isn’t to impress them; it’s to engage them.

They don’t need the perfect line. They need something to react to. Once you give them that, their choices start doing half the work for you.

Lightweight Prep That Supercharges Improv

The best prep I’ve found for improv is structural, not script-like. It gives me handles to grab when my brain stalls.

For a more improv-heavy session, I usually arrive with:

A situation, not a plot.

“Cultists and a rival scholar are racing to plunder the same ruined temple” is improvable. “Scene 3: PCs talk to Scholar, then travel, then ambush in canyon” is brittle. I want tensions, not storyboards.

A short cast list with moods and problems.

Rather than full stat blocks for ten NPCs, I prep a handful of names with one line of personality and one problem: “Professor Iqbal – charming, terrified the university will cut his funding.” That’s often enough to improvise their reactions and choices.

A few ‘pressure points’.

I like to know who might show up with bad news; what might explode if left alone; and what will happen if the PCs do absolutely nothing. That gives me pressure to apply on the fly.

Reusable tools.

A random names list. A few generic locations I can reskin. A page of prompts for “complications” or “twists”. This is very much in the spirit of the Lazy DM idea that the best prep is the prep that helps you improvise at the table.

None of this is heavy. It’s closer to a festival wristband than a cast-iron manacle.

Stop the Threads Unravelling: Reincorporation as a Superpower

The big fear with improv is that you throw out so many cool details that, two sessions later, the campaign looks like a drawer full of tangled cables.

The trick I’ve had most success with is aggressive reincorporation.

Whenever I invent something on the fly (a tavern name, a throwaway cult, an insulted baron), I ask myself, “How can I bring this back later and make it matter?”

If the players seem mildly interested, I bump it from “one-off detail” to “recurring motif” and start weaving it into existing threads. The mysterious sigil they spotted in Session 1 reappears on a letter in Session 3, then on a ceremonial dagger in Session 5. Suddenly it looks like design, not panic.

This does two things. First, it makes the world feel coherent, because callbacks mimic how real life patterns work. Second, it rescues all those improvised details from becoming loose ends. You’re sewing them back into the quilt, one by one.

Practically, I try to end each session by glancing over my notes and putting little stars by any improvised thing that got a reaction. Those are my “bring this back later” hooks.

Future Me loves Past Me for this. Present Me, alas, is usually between them apologising for my handwriting.

What Notes Actually Matter in Play

This is the part where I admit that, despite all my fancy campaign documents, my most valuable improv tools are scruffy session notes.

During an improv-heavy game, I consistently track five things:

First, any new names I invent: people, places, organisations, ships, cults, haunted sandwich shops. If I don’t write them down immediately, I will call the same NPC “Gareth”, “Galen”, and “Graeme” in the same evening.

Second, any new facts we establish about the world that might matter again: “The Duchess hates magic”, “the river floods every winter”, “there’s definitely something in the lake”. These are seeds I can grow later.

Third, any promises, threats, or debts that got spoken aloud: favours owed, deals struck, deadlines agreed. These are ready-made future complications.

Fourth, any emotional shifts between the PCs and important NPCs: who they currently trust, fear, resent, or adore. You don’t need a novel; a quick “Captain Wei: now grateful” is enough.

Finally, any unanswered questions that surfaced in play. “Who killed the prior?” “Why is the temple sealed?” “What’s really in the box?” I don’t have to know the answers yet, but if I write down the questions, I can build future sessions around resolving them.

That’s it. I don’t need full transcripts, nor does it all need to be perfectly organised on campaign wikis. I find the latter incredibly burdensome – good intentions that I just can’t keep going long term. What works for me is a thin trail of breadcrumbs to help me pretend I knew where I was going. I swear by post its and their digital equivalent (such as Trello). Often things start on paper and get put on a digital board for later reference.

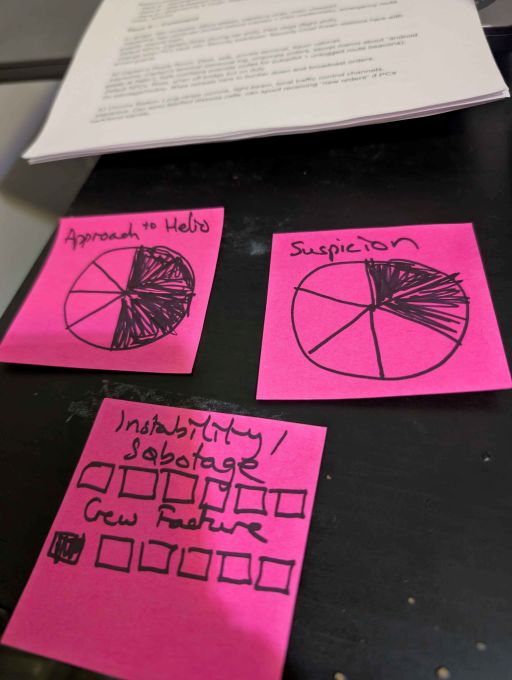

Clocks, Countdowns, and Attitude Trackers: Fake It ’Til Structure Emerges

One of the easiest ways to feel less lost while improvising is to give yourself simple, visible structures to hang decisions on. A lot of modern games lean on things like “clocks” and “fronts”; you can steal that thinking for anything.

A clock is just a circle you divide into slices and fill in as things progress. I might have a four-segment clock for “the cult completes the ritual”. Every time the PCs waste time, fail loudly, or ignore warning signs, I fill a segment. When it’s full, something happens on screen.

Because the clock is there, I don’t have to decide, in the moment, “Has the ritual finished yet?” I just look at the clock. I improvised the exact scenes, but the tempo comes from the countdown.

An attitude tracker is the same idea for NPC feelings. I jot a little scale next to a key NPC – hostile, wary, neutral, friendly, loyal – and mark where they start. When the PCs do something significant, I nudge the marker. Suddenly I have a history of that relationship, not just vibes.

Over time, these little trackers create emergent structure. You didn’t pre-write a story where the cult completes the ritual just as the PCs earn the captain’s loyalty… but that’s how the clocks landed, so that’s the climax you get. It feels organic, because it grew out of what actually happened.

And it means when you’re improvising the next scene, you’re not thinking, “What would be cool?” in a vacuum; you’re thinking, “Given these clocks and attitudes, what’s the next honest development?”

Improvising Mysteries Without Painting Yourself Into a Corner

Mysteries are where a lot of GMs bail on improv and retreat into twenty pages of flowcharts. I get it. The fear is, “If I make this up as I go, it’ll never make sense.”

The trick is to separate player experience from GM certainty.

You don’t always need to know the whole solution when the investigation starts. You just need to make sure the players are always finding something that feels meaningful and nudges them forward.

A lot of mystery advice online talks about the “three clue rule”: for any important conclusion, give the players multiple, redundant clues, so missing one doesn’t stall the game.That principle is your best friend when improvising.

Here’s how I often do it at the table:

I start by deciding a few possible answers to the central question. Maybe three people could plausibly have killed the prior. I don’t lock the final culprit yet.

As the players investigate, I improvise clues that point towards one or more of those suspects, always trying to give them more than one way to reach any given lead. If they get fascinated by one thread, I quietly start favouring that suspect as the “real” answer and make future clues line up.

From their perspective, they’re assembling a coherent picture from clues that were “obviously” planted in advance. From my perspective, I’m steering the solution towards whichever line of inquiry they’re most excited by, then tidying up the logic between sessions.

For on-the-spot riddles or puzzles, I keep my ambitions modest. I pick a mundane concept (fire, time, a key, a door), think of two or three distinctive qualities, and phrase those as a slightly purple description. If you’re stuck, you can always fall back on pattern-matching puzzles (“Which thing doesn’t fit?”) rather than riddles that rely on a specific wording.

And crucially, I always make sure there’s a non-puzzle way forward: an NPC hint, a brute-force alternative, or a consequence-laden shortcut. Nothing kills improv confidence faster than watching your cool made-up riddle slowly suffocate the session.

When Improv Goes Wrong (and It Will)

Sometimes you’ll contradict yourself. Sometimes you’ll forget a name. Sometimes you’ll improvise a scene that feels flat, and you’ll see your players’ attention drift towards their phones and/or the snack table.

A few things that have saved me:

Own the wobble.

If you’ve genuinely stepped on your own continuity, it’s fine to say, “Hang on, I misspoke there – can we treat that as X instead?” Most groups are happy to accept a small retcon if it keeps the big picture intact.

Use time skips as a reset button.

If an improvised thread has gone nowhere interesting, wrap it. “After an hour of going in circles with the guard captain, you’re no closer to an answer… but now it’s midnight and the city is quiet.” Cut, move to a new scene, bring in a fresh angle.

Promote your mistakes.

Occasionally, a bad or silly improv choice can be reframed as intentional foreshadowing. That weird non-answer from the priest? Maybe they were lying. That awkward pause? Maybe they were hiding something. You can retroactively decide that your own flailing was actually the character’s.

Let the players rescue you.

If someone at the table suggests a theory more interesting than anything you had planned, steal it with gratitude. High Level Games talks about how improvisation can “remove the laborious parts of our hobby and let us focus on the parts we really enjoy.” One of those enjoyable parts is shamelessly repurposing your players’ best ideas.

You’re Allowed To Be a Work in Progress

I’m not some improv ninja who can effortlessly spin golden story-threads every session. I still over-prep sometimes because it makes me feel safe. I still stare at my notes thinking, “Why did I think three intersecting conspiracies was a good idea?”

But the more I lean into improv, the more I realise a few reassuring truths:

Players remember how they felt, not how perfectly you foreshadowed Act Three. The big emotional moments (the desperate bargain, the unexpected betrayal, the sudden triumph) are just as likely to come from improvised scenes as from your best-laid plans. Robin Laws talks about learning to rapidly review outcomes and respond at the table, not to flawlessly execute a pre-written script.

Your elaborate Children of Fear node graph and your “I have three names on a Post-it” one-shot live in the same place in your players’ heads: Did we have fun? Did it feel like our choices mattered?

Improv isn’t a test of cleverness; it’s a skill you can practice. Each time you trust yourself to make a thing up and then catch it with good notes, clocks, and reincorporation, you nudge that skill up a notch.

So if you’re improv-shy, here’s my gentle take-away message:

Next session, pick one thing to loosen your grip on. Maybe you prep a situation instead of a plot. Maybe you decide not to script any dialogue. Maybe you try using one simple clock. See what happens. Take notes. Bring something back next time.

We can learn this together. I’m still very much in the “scribbling frantically between scenes and pretending I meant it” stage, but the games are better for it.

And your players? They’ll just think you’re incredibly organised.